Does it help to know your type? The notion of personality preferences is not controversial - we all have our likes and dislikes - but the notion that we fit into a "type" or a "style" is controversial because it suggests that once I know your type, I can make predictions about you. It means that I can suggest what kind of world where you should live, work, and love in order to optimize your happiness and productivity (1). People also resist personality typing because it means that they should fit into a box drawn by a dead white guy. (It's worth noting that MBTI was created by a mother-daughter team and they had no training in psychology Academics hate it for that reason too!) Nonetheless, tests of styles, and types are very, very popular - especially in business, education, and fashion magazines. There are tests for management styles, learning styles, attachment styles, productivity styles, conflict styles, leadership types, and so many more. The idea that once you know your type or style, you can tailor your life to match it is big business!

References & Resources

0 Comments

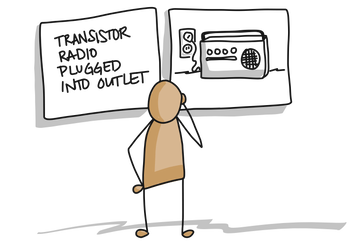

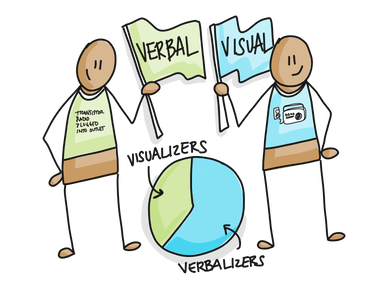

So, does this make me a “visual learner”? When people talk about learning styles, they often refer to people who prefer to learn from visual information (i.e., drawings, photographs, diagrams, and illustrations) and people who prefer to learn from verbal information (i.e., spoken words, written stories, and text-based instructions). Hence the suggestion of two learning styles: “visualizer” and “verbalizer”. These two styles have received a lot of attention from academic researchers, parenting journals, and Facebook quizzes, but they are only two among dozens of learning styles have been described over the years (e.g., Myers-Briggs, Kolb’s Learning Styles, Gardner’s Multiple Intelligences, etc.). It seems to give people reassurance when they believe they know how they learn best. Parents are also drawn to the idea that if their children are taught in their preferred learning style, they will do better in school and go on to live more successful lives. However, the science suggests that it is not this simple (1). Educational psychologists have documented that people do indeed prefer visual or verbal information and to some degree these preferences are related to their cognitive ability with visual or verbal information (2). Scientists determine someone’s preference by giving them a quiz that asks questions like: “when you read science lab manual, do you prefer to look at the diagrams or read the text?” Once they know a person’s preferred style, they can validate that preference by offering them the choice of multiple types of information (i.e. diagrammatic or text-based help on a quiz) and determining if their choices match their preference (1). Once researchers demonstrate that people reliably prefer one type of information over another, they need to figure out if people learn better in an environment that emphasizes the type of information that they prefer (3). This distinction – switching from identifying the information I prefer to the information that helps me learn – is what separates a learning preference from a learning style. Researchers call this the “meshing hypothesis” and is the most common way to test for the existence of learning styles (4). Tests of the meshing hypothesis have come up empty-handed. Students do not score better on quizzes after they have been taught in their preferred style (5, 6). In one study, the researchers found that all learners performed slightly better on a quiz about lightning formation when they were presented with visual information, regardless of their learning preference. It seems that students can adapt to accommodate any type of information presentation. While there is not much scientific support for the meshing hypothesis, there is support for the idea that the teaching method should match the content being taught (7). For example, how effective would it be to teach:

The idea of learning styles is very compelling because it speaks to our human desire to understand ourselves and be understood. However, it is important to understand the difference between preferring visual information and learning more effectively from visual information because if you believe too strongly that you need visual information to learn, you could miss out on a lot of exciting ideas that are best described in only in words! Resources & References

|

Details

Categories

All

Angie B. Moline

Dr. Moline is an ecologist and visual process facilitator who draws pictures to help clients think. She is currently on a quest to understand why live drawings are so compelling and how to make them as sticky as possible in order to improve communication, understanding, and memory. Follow here journey here! |

strategy

innovation

Communication

Clients & Case Studies

philanthropy

ABOUT US

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed